Reactions to the release of Pussy Riot's Yekaterina

Samutsevich have generally been myopic and misleading. The popular

“insight” from experts and amateur observers alike has been that the

authorities are maneuvering to “divide and conquer” the punk rocker trio. That is undoubtedly part of what's happened, but it isn't the whole story.

By freeing Samutsevich, the Russian government has achieved two distinct objectives in its battle against the protest movement: differentiation and proportionality. “Divide and conquer” describes the first concept, but it doesn't capture the latter, which is just as vital to the state's efforts to stymie the opposition.

Consider how Samutsevich was able to overturn her original prison sentence. She fired her lawyer, Violetta Volkova, and hired Irina Khrunova, who asked [ru] the judge to recognize that Samutsevich had never actually managed to “dance, sing, cry out, or do anything [in the church] that the court had qualified as a crime.” Writing in Bolshoi Gorod magazine, Kirill Rogov argued [ru] that Khrunova essentially appealed to Vladimir Putin's interpretation of the case (that the defendants' misdeeds occurred only inside the Cathedral of Christ the Savior).

In other words, the anti-Putin lyrics later dubbed over video footage

of the church incident (see video below) did not constitute a crime:

only the actions committed inside the church were criminal. Because

security guards intercepted Samutsevich before she could join her fellow

band members at the altar, she never jumped, gesticulated, or otherwise

exuded any religious hatred, says the narrative.

In other words, the anti-Putin lyrics later dubbed over video footage

of the church incident (see video below) did not constitute a crime:

only the actions committed inside the church were criminal. Because

security guards intercepted Samutsevich before she could join her fellow

band members at the altar, she never jumped, gesticulated, or otherwise

exuded any religious hatred, says the narrative.

Samutsevich's release sends many messages. The one bloggers and journalists have mostly picked up on is that “it's now everyone for herself” in the Pussy Riot case. This Prisoner's Dilemma is usually acknowledged disappointedly. (Think of the many disenchanted accusations levied at Samutsevich that she “struck a deal” with the authorities and effectively betrayed her compatriots. You can find this sentiment in Facebook posts by Evgeniia Albats [ru], Tikhon Dziadko [ru], and many others [ru].) More irreverent voices have welcomed Pussy Riot's split as the overdue arrival of “common sense” on the part of Samutsevich. (Dmitri Olshanskii used this exact phrase [ru], and others [ru] have implied as much in attacks on the band's three original lawyers.) While nearly everyone in the opposition has applauded the fact that a Pussy Riot inmate is now free, the divide between “disappointed” and “overdue” celebration is real.

This angle, however, fails to capture the proportionality aspect of the government's latest move. Driving a wedge between Pussy Riot's supporters and sympathizers is just one facet of yesterday's court decision. Samutsevich's release also signals that the state will respond varyingly to various types of protest. Less disruptive behavior, it turns out, will be punished less. This is a novelty for the case. So far, the Pussy Riot trial as a Russian social event has communicated only threats to the country's protest movement. “Any kind of unconventional demonstrations won't be tolerated,” the memo read.

The authorities have now refined that message. As a result, the reasons for moderate protesters (or indeed the general public) to support the remaining Pussy Riot inmates are fewer. Before Samutsevich's release, the band's cause had an urgency that accompanied their apparent blanket persecution. All three members had been convicted and sentenced identically, despite the fact that Samutsevich had technically “done less.” This conveyed to citizens that any cooperation whatsoever with protests as unconventional as Pussy Riot's would be repressed unconditionally.

Will the band's exalted status now change? In the aftermath of yesterday's events, many activists fervently denied that possibility. “She just got lucky,” Kommersant's Demian Kudriavtsev explained [ru]. “Nothing has changed,” journalist-blogger Oleg Kashin wrote [ru] unflappably. “It's just that Yekaterina Samutsevich is now free,” he added.

Indeed, things had changed so little that Kashin felt compelled to pen two separate op-eds within 24 hours of Samutsevich's release. In his other composition [ru], he likened the Moscow court to Chechen terrorists and compared Pussy Riot to Shamil Basayev's hostages in the 1995 Budyonnovsk hospital standoff (which resulted in the deaths of over 100 people).

Kashin's parallel should alarm his readers. If Budyonnovsk is his idea of “nothing happening,” Russia's future is muddy indeed.

Written by Kevin Rothrock Global Voices

By freeing Samutsevich, the Russian government has achieved two distinct objectives in its battle against the protest movement: differentiation and proportionality. “Divide and conquer” describes the first concept, but it doesn't capture the latter, which is just as vital to the state's efforts to stymie the opposition.

Consider how Samutsevich was able to overturn her original prison sentence. She fired her lawyer, Violetta Volkova, and hired Irina Khrunova, who asked [ru] the judge to recognize that Samutsevich had never actually managed to “dance, sing, cry out, or do anything [in the church] that the court had qualified as a crime.” Writing in Bolshoi Gorod magazine, Kirill Rogov argued [ru] that Khrunova essentially appealed to Vladimir Putin's interpretation of the case (that the defendants' misdeeds occurred only inside the Cathedral of Christ the Savior).

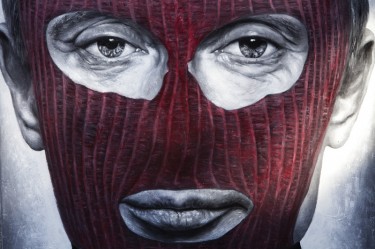

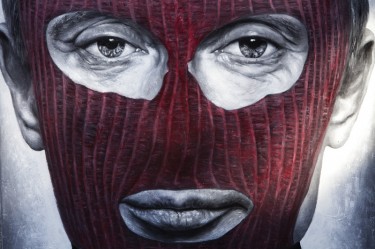

Pussy

Riot, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, painted portrait in St. Romain,

Rhone-Alpes, France (7 June 2012), photo by Thierry Ehrmann, CC 2.0.

Samutsevich's release sends many messages. The one bloggers and journalists have mostly picked up on is that “it's now everyone for herself” in the Pussy Riot case. This Prisoner's Dilemma is usually acknowledged disappointedly. (Think of the many disenchanted accusations levied at Samutsevich that she “struck a deal” with the authorities and effectively betrayed her compatriots. You can find this sentiment in Facebook posts by Evgeniia Albats [ru], Tikhon Dziadko [ru], and many others [ru].) More irreverent voices have welcomed Pussy Riot's split as the overdue arrival of “common sense” on the part of Samutsevich. (Dmitri Olshanskii used this exact phrase [ru], and others [ru] have implied as much in attacks on the band's three original lawyers.) While nearly everyone in the opposition has applauded the fact that a Pussy Riot inmate is now free, the divide between “disappointed” and “overdue” celebration is real.

This angle, however, fails to capture the proportionality aspect of the government's latest move. Driving a wedge between Pussy Riot's supporters and sympathizers is just one facet of yesterday's court decision. Samutsevich's release also signals that the state will respond varyingly to various types of protest. Less disruptive behavior, it turns out, will be punished less. This is a novelty for the case. So far, the Pussy Riot trial as a Russian social event has communicated only threats to the country's protest movement. “Any kind of unconventional demonstrations won't be tolerated,” the memo read.

The authorities have now refined that message. As a result, the reasons for moderate protesters (or indeed the general public) to support the remaining Pussy Riot inmates are fewer. Before Samutsevich's release, the band's cause had an urgency that accompanied their apparent blanket persecution. All three members had been convicted and sentenced identically, despite the fact that Samutsevich had technically “done less.” This conveyed to citizens that any cooperation whatsoever with protests as unconventional as Pussy Riot's would be repressed unconditionally.

(Unedited video of Pussy Riot's performance at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 21 February 2012.)

The authorities' calculation was presumably to scare more extreme

protesters into backing down. Whether or not that was their intention,

the trial did not subdue or silence much of anyone. Instead, it heaped

celebrity on Pussy Riot, transforming them into martyrs of Russian civil

society at large. Yes, some dissidents refused to embrace the band as a

symbol for their movement (elderly human rights activist Liudmila

Alexeyeva has bemoaned [ru]

the attention paid to their case, for instance), but the general trend

has certainly been to treat Pussy Riot as the bellwether of freedom in

Russia today.Will the band's exalted status now change? In the aftermath of yesterday's events, many activists fervently denied that possibility. “She just got lucky,” Kommersant's Demian Kudriavtsev explained [ru]. “Nothing has changed,” journalist-blogger Oleg Kashin wrote [ru] unflappably. “It's just that Yekaterina Samutsevich is now free,” he added.

Indeed, things had changed so little that Kashin felt compelled to pen two separate op-eds within 24 hours of Samutsevich's release. In his other composition [ru], he likened the Moscow court to Chechen terrorists and compared Pussy Riot to Shamil Basayev's hostages in the 1995 Budyonnovsk hospital standoff (which resulted in the deaths of over 100 people).

Kashin's parallel should alarm his readers. If Budyonnovsk is his idea of “nothing happening,” Russia's future is muddy indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment