Azerbaijan's recent oil boom

has given the Aliyev dynasty a chance to tighten its grip on power.

Since the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline began to funnel Azeri oil into

European markets six years ago, this small former-Soviet state has been

producing more than a million barrels of oil each day. The sudden

quadrupling of its oil production has allowed the regime to buy more

domestic and international support, and store up repressive capacity for

the post-oil era. The remnants of the weakly competitive pre-oil-boom

era were erased in the 2010 parliamentary elections, when real

opposition candidates gained none of the 125 seats.

Azerbaijan's recent oil boom

has given the Aliyev dynasty a chance to tighten its grip on power.

Since the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline began to funnel Azeri oil into

European markets six years ago, this small former-Soviet state has been

producing more than a million barrels of oil each day. The sudden

quadrupling of its oil production has allowed the regime to buy more

domestic and international support, and store up repressive capacity for

the post-oil era. The remnants of the weakly competitive pre-oil-boom

era were erased in the 2010 parliamentary elections, when real

opposition candidates gained none of the 125 seats.But the Arab spring has stirred up some trouble on the western shores of the Caspian as well. Dozens of opposition activists are standing trial for attempting to hold rallies in Baku. Last week, a youth activist was handed a two-and-a-half-year sentence on drug possession charges. The fact that his arrest came only a day after posting Facebook notes calling on his friends to launch Egyptian-style youth protests cast serious doubt on credibility of his trial. Another youth activist, this time a Harvard graduate and parliamentary candidate, is standing trial for draft evasion charges.

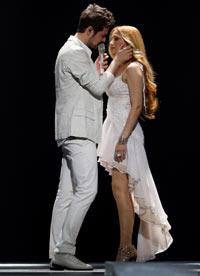

Nonetheless, there is a possibility that Eurovision will not only halt this wave of repression fuelled by petrodollars and Ilham Aliyev's anxiety over the Arab spring, but also usher in a little bit of political openness. This could happen in five different ways.

First, Azerbaijan will have to revert to the system of issuing visas at the airport, which was replaced last year amid the regime's concerns over global rights activists and critical journalists entering the country. The present rule gives the government the time required to screen out those known for criticising the country's human rights record and reject or delay their visa applications. However, this will have to change as Azeri embassies in major European capitals are not big enough to handle the hundreds of visa applications per week that Eurovision will generate.

Second, the rulers will have to learn some degree of administrative efficiency. Transparency International has consistently ranked Azerbaijan among the most corrupt states in the world – even more corrupt than states like Iran, Libya and Pakistan. If the government wants to match Germany's performance in hosting the event, it will need to embark on a massive infrastructure-strengthening project. To achieve results in just a year, it will have to spend more time preparing for hosting Eurovision and less time embezzling funds allocated for improving the Eurovision infrastructure. Otherwise, in the spring of 2012, the government will face a public humiliation that authoritarian regimes can little afford.

Third, in the weeks leading to the competition, the country will come under the kind of European spotlight that it has never experienced before. Naturally, this will increase awareness of Azerbaijan and produce results that many expected of the Beijing Olympics in 2008. There are reasons to assume that Eurovision can do for Azerbaijan what the Olympics could not do for China – namely, compel it to reform its international image as an authoritarian state. For unlike the Olympics' focus on difference and its avowed apolitical nature, Eurovision is a European project that has an exclusively European audience. Moreover, as a weaker state, Azerbaijan is much less able to show a China-like resistance to international attention on its human rights record.

Fourth, there will be more gatherings in the streets of Baku, which means that the regime will have to break its anxious habit of sending police officers whenever a handful of youths gather in public.

Last, but not least, the large crowds that the Eurovision victory brought to the streets of Baku showed that decades of authoritarian rule has not been able to quell the spontaneous expression of collective joy, and possibly anger. Days like this remind the ruling family that the people of Azerbaijan, especially its youth, have not lost touch with collective aspirations.

All of this actually shows how easy it can be to stimulate political change in some of the softer authoritarian states. Eurovision has presented its 150-million-strong European audience an opportunity to help bring a little bit of openness to one of Europe's two remaining dictatorships.

No comments:

Post a Comment